Small parcel shippers understand the nature of the General Rate Increase, and they best attempt to mitigate the increase accordingly. We, as shippers, understood the dimensional weight logic to change in 2015, and ideally we were preparing for several months to ensure our invoiced costs and negotiated divisors most accurately reflected our actual shipping profile. Now that the smoke is clearing we are getting a look at who took a financial hit and what alternatives exist that create savings through durability, not just the divisor. The logic changed — did shipping patterns change?

Cube Utilization

When considering dimensional impact, and more so how to offset it, we must first understand cube utilization. We can go fast and furious and attack the dimensional divisor itself, but few shippers get the divisor waived. Instead of immediately targeting the surcharge let’s understand what drives it—and how we can eliminate it outside of the contract.

Cube utilization is the use of space within a container or box — a percentage of total usable space. The average e-commerce shipper achieves 60-65% cube utilization on outbound boxes. This means that package has 35-40% of its inner space occupied by fillers or air. Unfortunately you aren’t paying peanuts to ship those foam peanuts.

We want to consider the concept of unitizing as we utilize. Unitizing a shipment or load is taking smaller packages (units) and putting them in a larger package or system to move the shipment easier—the goal being to pack the shipment and use the space in the container efficiently with product. If a product is not designed correctly shippers then need to adjust packaging to offset poor product design.

Product Durability versus Package Performance

A significant area of review in transportation cost management is packaging optimization. Shock, vibration, compression—this is what your package is exposed to each time it gets sorted in a hub or station and loaded on the van. A package traveling a mere couple hundred miles may be loaded and reloaded as frequently as five times between truck, terminal, and hub. Carriers offer definite delivery times so these packages need to be scanned quickly and moved to the next destination. Therefore package handlers will sort the packages in a manner the keeps the center of gravity low, so the package is not top heavy and risks falling off the belt, and keeps the label visible at all times.

Package handlers do not stack one package on top of the next in a columnar fashion but rather the packages are interlocked. The goal — to securely move as many packages as quickly as possible. The concern — compression. Corrugated box strength, when interlocked in transit instead of column stacked, reduces by up to 50%. Handlers try to keep the heavier packages on the bottom of the stack, but since packages are stacked and loaded as they are received, smaller less dense packages are subject to supporting the weight of the package wall.

Compression is not exclusive to stacking. When a sortation belt jams packages can slam into each other and continue to press together until the jam is alleviated or the belt is turned off. Compressive forces can impact the top and bottom as well as the sides of the package. Palletized packages are frequent victims of dynamic compression, which is why shippers are encouraged to consult their carrier’s package testing lab to verify the durability and sustainability of the package composition before using it to send merchandise. As shippers we want to cut dimensional cost by under designing the package. Seemingly makes sense for cost containment—less wasted package space, less billed weight. But if your product lacks durability, what you save in packaging you spend in replacement freight, fees, and fuel.

If you are at 50 percent of your strength you are also at 50% of your support, which now introduces the elements of shock and vibration. Shock occurs when a package is dropped or rattled by another package. Packages rarely fall flat; they normally strike an edge or corner or hit the bottom surface of the package when they land. This impact can cause abrasions to the package surface or tear the packaging entirely, now subjecting the contents to damage. To ensure some level of protection a two inch buffer should be allowed on each side between the product and the packaging. Anything greater than two inches then introduces package over design. Waste of packaging and increase of costs though materials, dimensional impact, and possibly storage.

As trucks, aircraft, and sortation belts move they create levels of vibration. Vibration varies from a steady constant hum to a several pinpointed sharp jolts. Packages on a trailer driving cross country are subject to vibration for days. This constant movement can loosen closures and weaken packaging as well as shift the package contents, resulting in pressure points on the box, bag, or container.

Two additional packaging hazards to consider are climate and altitude. Contractor vans are not air conditioned so if it is 100 degrees outside the van it is 100 degrees inside the van. Likewise if the van is traveling through below zero temperatures the packages are below freezing as well. Most cargo jets are pressurized, but trucks can hit altitudes over 10,000 feet.

How did we weather the dimensional storm?

Why, as shippers, do we need to care about all of this? Because package optimization drives dimensional costs, and shippers are feeling the burn of the new logic. The burn isn’t universal, though.

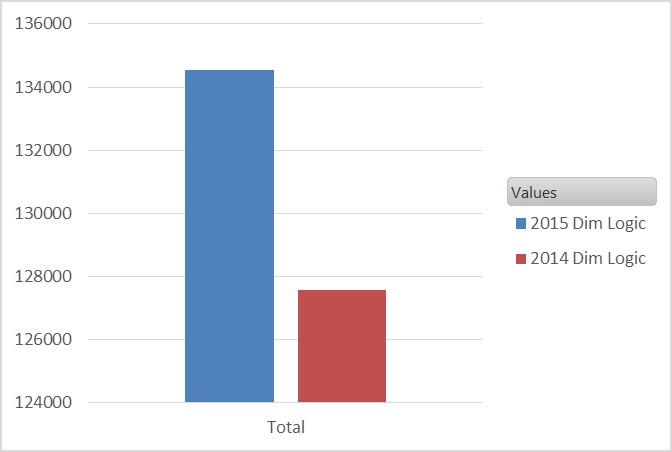

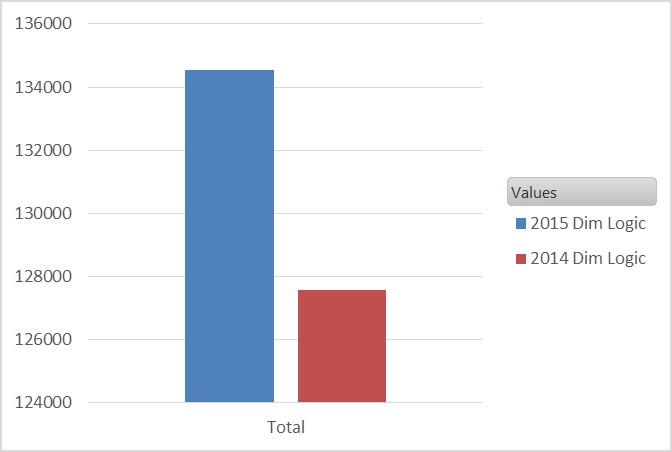

Chart A represents the dollar impact of the dimensional logic change for a $3MM shipper, based on a four week snapshot of data. Because this shipper had previously negotiated a 250 divisor, the impact is minimal for this month at a little under $7K. While this shipper did see more packages invoice at higher billed than actual weights, the already strong divisor lessened the gap. We can annualize the numbers, and assuming the shipping profile remains constant, see a year end increase of $84K.

Chart A

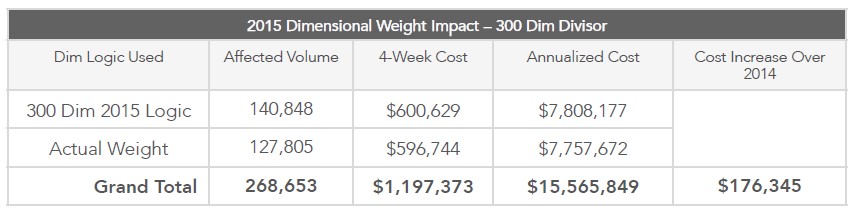

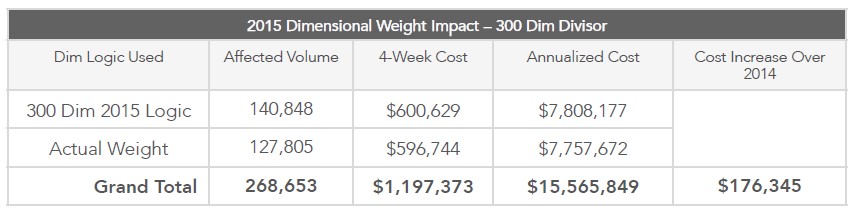

Chart B shows a dimensional dilemma and highlights why shippers cannot rest on divisor relief alone. We must control costs through contract optimization and supply chain optimization. The company shown below has a 173 dim, and as we can see through the analysis, will face a cost increase over $2MM with the 2015 logic change.

As we negotiate through the divisors we see that $2MM reduce down to less than $200K. This client cannot just “suck up” a $2MM increase so we would consider dimensional waivers based on account number or a freeze in the logic change. We also want to consider negotiating the billed weights to offset the increase in cost.

Attack the data, not the divisor

The challenge for many shippers is knowing what dimensions exist in their warehouses, and what the actual weights of those packages are. We receive manifests of tracking numbers and associated dimensions, but without knowing actual weight, we will be challenged to adequately quantify the potential cost increase. And many warehouses do not own or lack the manpower to employ software to capture and store the data. How are shippers handling the new logic? They are looking to cubing and weighing systems.

Automated dimensioning systems optimize freight handling by quickly and accurately obtaining package dimensions, storing the shipment data, and allowing shippers to rapidly sort and target problem packages. We see static systems — collecting data on stationary items and sending the metrics to the warehouse for freight manifesting. But packages move so we need a way to review data when the boxes travel on conveyor belts. As we discussed above, packages fall, stack, and smash so the shape of the package at pick up can drastically change during sortation and delivery. If the shape changes, the dimensions can change, and now your billed weight can change even if the package just went a mile down the road to the local station. By using in motion scanning systems shippers can review length, width, and height — one cubing company offering a system that will measure the parcel’s data at speeds up to 600 feet per minute.

Key Takeaway

Shippers are feeling the dimensional logic pinch — we knew they would. We need to be mindful the carriers changed the operational cost of doing business, not just the financial cost. When a carrier looks at your actual package differently we need to look at the impact of poor design. We can negotiate a solid dimensional divisor, but if package performance is weakened, so is our expected savings.

Brittany Beecroft is Director of Parcel Pricing for AFS. In her position, she oversees Parcel Cost Management and RFP processes for the purpose of negotiating and retaining best-in-class client-specific pricing. Brittany also provides training and guidance to sales and the support staff to manage parcel cost reduction and optimization services. Prior to joining AFS, she spent 12 years as a Strategic Pricing Analyst at FedEx. Brittany consults regularly with some of the largest shippers in the world and is a sought-after speaker and consultant.

Cube Utilization

When considering dimensional impact, and more so how to offset it, we must first understand cube utilization. We can go fast and furious and attack the dimensional divisor itself, but few shippers get the divisor waived. Instead of immediately targeting the surcharge let’s understand what drives it—and how we can eliminate it outside of the contract.

Cube utilization is the use of space within a container or box — a percentage of total usable space. The average e-commerce shipper achieves 60-65% cube utilization on outbound boxes. This means that package has 35-40% of its inner space occupied by fillers or air. Unfortunately you aren’t paying peanuts to ship those foam peanuts.

We want to consider the concept of unitizing as we utilize. Unitizing a shipment or load is taking smaller packages (units) and putting them in a larger package or system to move the shipment easier—the goal being to pack the shipment and use the space in the container efficiently with product. If a product is not designed correctly shippers then need to adjust packaging to offset poor product design.

Product Durability versus Package Performance

A significant area of review in transportation cost management is packaging optimization. Shock, vibration, compression—this is what your package is exposed to each time it gets sorted in a hub or station and loaded on the van. A package traveling a mere couple hundred miles may be loaded and reloaded as frequently as five times between truck, terminal, and hub. Carriers offer definite delivery times so these packages need to be scanned quickly and moved to the next destination. Therefore package handlers will sort the packages in a manner the keeps the center of gravity low, so the package is not top heavy and risks falling off the belt, and keeps the label visible at all times.

Package handlers do not stack one package on top of the next in a columnar fashion but rather the packages are interlocked. The goal — to securely move as many packages as quickly as possible. The concern — compression. Corrugated box strength, when interlocked in transit instead of column stacked, reduces by up to 50%. Handlers try to keep the heavier packages on the bottom of the stack, but since packages are stacked and loaded as they are received, smaller less dense packages are subject to supporting the weight of the package wall.

Compression is not exclusive to stacking. When a sortation belt jams packages can slam into each other and continue to press together until the jam is alleviated or the belt is turned off. Compressive forces can impact the top and bottom as well as the sides of the package. Palletized packages are frequent victims of dynamic compression, which is why shippers are encouraged to consult their carrier’s package testing lab to verify the durability and sustainability of the package composition before using it to send merchandise. As shippers we want to cut dimensional cost by under designing the package. Seemingly makes sense for cost containment—less wasted package space, less billed weight. But if your product lacks durability, what you save in packaging you spend in replacement freight, fees, and fuel.

If you are at 50 percent of your strength you are also at 50% of your support, which now introduces the elements of shock and vibration. Shock occurs when a package is dropped or rattled by another package. Packages rarely fall flat; they normally strike an edge or corner or hit the bottom surface of the package when they land. This impact can cause abrasions to the package surface or tear the packaging entirely, now subjecting the contents to damage. To ensure some level of protection a two inch buffer should be allowed on each side between the product and the packaging. Anything greater than two inches then introduces package over design. Waste of packaging and increase of costs though materials, dimensional impact, and possibly storage.

As trucks, aircraft, and sortation belts move they create levels of vibration. Vibration varies from a steady constant hum to a several pinpointed sharp jolts. Packages on a trailer driving cross country are subject to vibration for days. This constant movement can loosen closures and weaken packaging as well as shift the package contents, resulting in pressure points on the box, bag, or container.

Two additional packaging hazards to consider are climate and altitude. Contractor vans are not air conditioned so if it is 100 degrees outside the van it is 100 degrees inside the van. Likewise if the van is traveling through below zero temperatures the packages are below freezing as well. Most cargo jets are pressurized, but trucks can hit altitudes over 10,000 feet.

How did we weather the dimensional storm?

Why, as shippers, do we need to care about all of this? Because package optimization drives dimensional costs, and shippers are feeling the burn of the new logic. The burn isn’t universal, though.

Chart A represents the dollar impact of the dimensional logic change for a $3MM shipper, based on a four week snapshot of data. Because this shipper had previously negotiated a 250 divisor, the impact is minimal for this month at a little under $7K. While this shipper did see more packages invoice at higher billed than actual weights, the already strong divisor lessened the gap. We can annualize the numbers, and assuming the shipping profile remains constant, see a year end increase of $84K.

Chart A

Chart B shows a dimensional dilemma and highlights why shippers cannot rest on divisor relief alone. We must control costs through contract optimization and supply chain optimization. The company shown below has a 173 dim, and as we can see through the analysis, will face a cost increase over $2MM with the 2015 logic change.

As we negotiate through the divisors we see that $2MM reduce down to less than $200K. This client cannot just “suck up” a $2MM increase so we would consider dimensional waivers based on account number or a freeze in the logic change. We also want to consider negotiating the billed weights to offset the increase in cost.

Attack the data, not the divisor

The challenge for many shippers is knowing what dimensions exist in their warehouses, and what the actual weights of those packages are. We receive manifests of tracking numbers and associated dimensions, but without knowing actual weight, we will be challenged to adequately quantify the potential cost increase. And many warehouses do not own or lack the manpower to employ software to capture and store the data. How are shippers handling the new logic? They are looking to cubing and weighing systems.

Automated dimensioning systems optimize freight handling by quickly and accurately obtaining package dimensions, storing the shipment data, and allowing shippers to rapidly sort and target problem packages. We see static systems — collecting data on stationary items and sending the metrics to the warehouse for freight manifesting. But packages move so we need a way to review data when the boxes travel on conveyor belts. As we discussed above, packages fall, stack, and smash so the shape of the package at pick up can drastically change during sortation and delivery. If the shape changes, the dimensions can change, and now your billed weight can change even if the package just went a mile down the road to the local station. By using in motion scanning systems shippers can review length, width, and height — one cubing company offering a system that will measure the parcel’s data at speeds up to 600 feet per minute.

Key Takeaway

Shippers are feeling the dimensional logic pinch — we knew they would. We need to be mindful the carriers changed the operational cost of doing business, not just the financial cost. When a carrier looks at your actual package differently we need to look at the impact of poor design. We can negotiate a solid dimensional divisor, but if package performance is weakened, so is our expected savings.

Brittany Beecroft is Director of Parcel Pricing for AFS. In her position, she oversees Parcel Cost Management and RFP processes for the purpose of negotiating and retaining best-in-class client-specific pricing. Brittany also provides training and guidance to sales and the support staff to manage parcel cost reduction and optimization services. Prior to joining AFS, she spent 12 years as a Strategic Pricing Analyst at FedEx. Brittany consults regularly with some of the largest shippers in the world and is a sought-after speaker and consultant.