It’s easy to look at the results of this year’s Shipware/PARCEL survey and conclude that aggressive cost increases by UPS and FedEx, plus the growing disparity in power between shippers and their carriers, are the main storylines. But buried underneath the easy headlines is something more exciting: true alternatives to FedEx and UPS are becoming viable — even popular.

CARRIER RATE INCREASES FORCING CHANGE

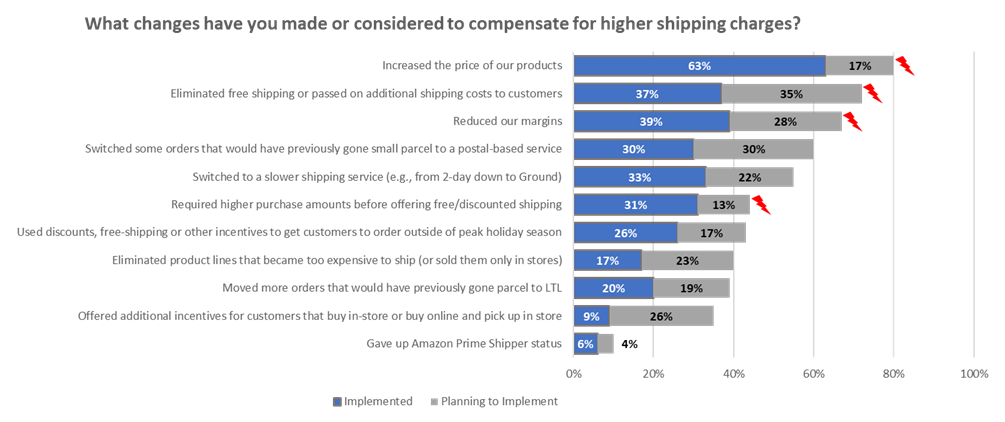

Respondents to this year’s survey suggest that UPS and FedEx are negatively impacting shippers’ bottom lines and the spending power of the American public. When asked if the accelerated rise in shipping rates since 2020 had forced them to make changes to their business, 82% of respondents said yes. Combining the “implemented” or “planning to implement” responses to certain changes made in response to carrier rate increases, 80% increased the price of their products, 72% charged more for shipping, 67% reduced their own margins, and 44% required higher purchase amounts before offering shipping discounts (see Figure 1).

If everyone were in this together, these sacrifices could be easily justified, but UPS achieved record-high profits during the same period, resulting from multiple pricing actions, downsizing, and service degradation. Entry-level economics textbooks suggest that only monopolistic pricing power, collusion, or profiteering could explain such aggressive price increases during a global pandemic for the sake of record profits (if shippers had options, wouldn’t they switch?), but UPS CEO Carol Tomé would certainly argue a more nuanced interpretation.

FIGURE 1:

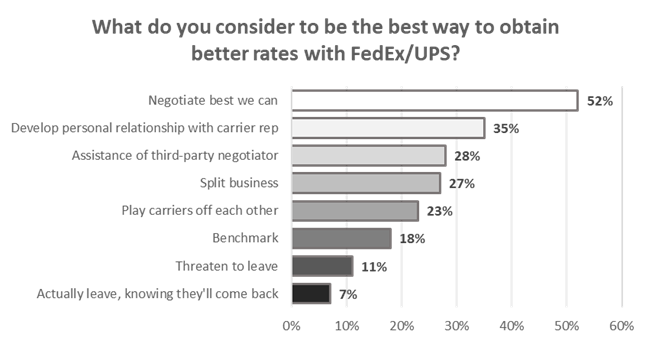

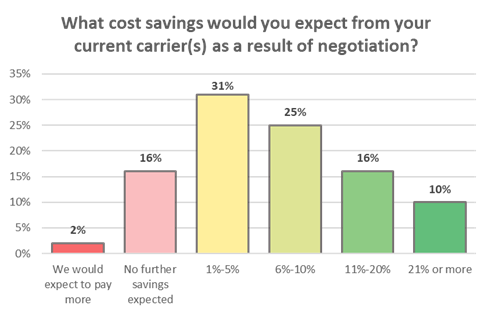

SHIPPERS FEEL HELPLESS

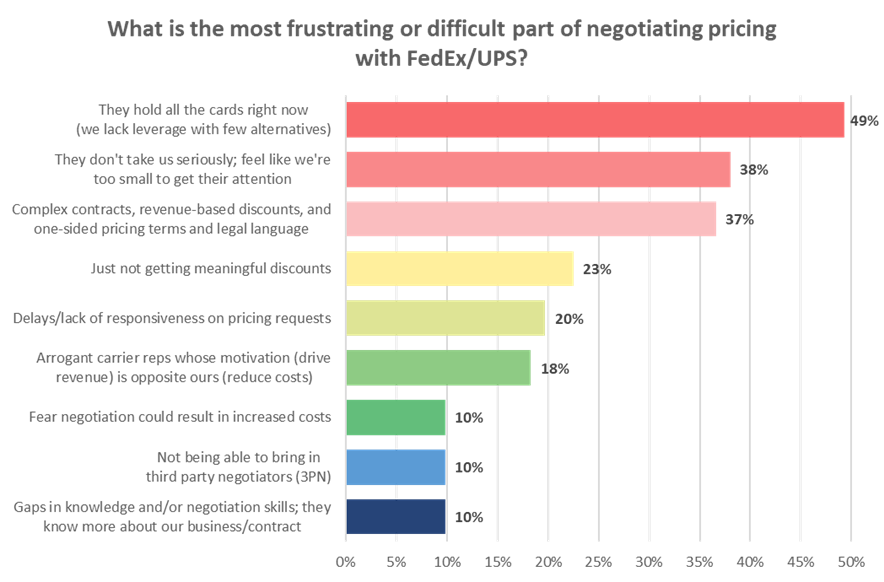

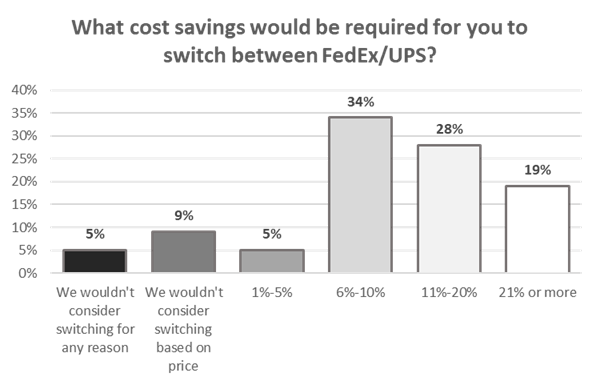

Almost half of respondents (49%), believed that UPS and FedEx held all the cards throughout 2021 and into 2022, and that they, the shipper, had few alternatives and little negotiating leverage (see Figure 2). Perhaps as a result, loyalty to a carrier is low, with only five percent unwilling to leave their current carrier for any reason (see Figure 3). Conversely, almost 40% reported being willing to switch for so little savings (10% or less) that switching costs might outweigh any shipping savings in Year 1.

Among respondents, the same number were loyal to UPS, FedEx, and the USPS, despite UPS being the primary carrier almost twice as often – 42%, 24%, and 24%, respectively, while two percent reported their primary carrier being a regional, three percent chose postal consolidators, and five percent of respondents choosing “other.” This is a concerning but predictable trend for UPS, which traditionally justified its higher prices by promising higher-value partnership. Since taking over as UPS CEO in mid-2020, and consistent with her early years as CFO at The Home Depot, Carol Tomé has commoditized customers and employees, eliminating much of what differentiated UPS from its competition, while still demanding a premium. This Six Sigma-like approach to human interaction is reminiscent of what caused UPS Teamsters to strike in 1997, and similar results are already unfolding.

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 3A:

Figure 3B: 18% of respondents expect no savings (or even worse!) if they pursue contract negotiations with their existing carrier.

THE ENTITLED PUSH AND PULL

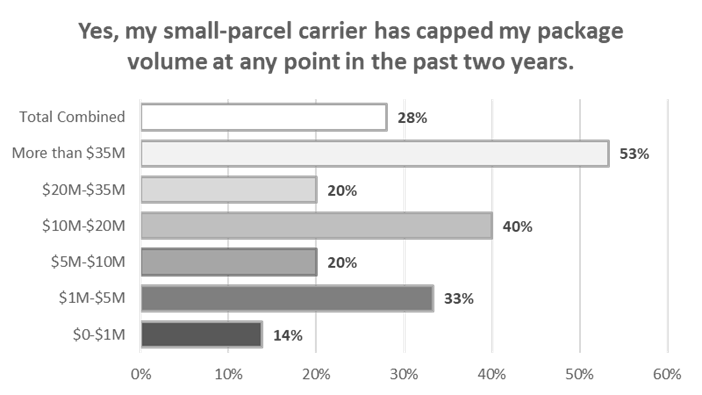

UPS and FedEx capped package volume unexpectedly in late 2020 (28% of respondents reported experiencing it, and of these respondents who answered yes, 14% were from companies that spent less than $1 million per year, as you can see from Figure 4). These are private, for-profit networks, but while no one questions their right to control the packages they are willing to accept, the difficulty for many affected companies was how these caps were applied, and what happened afterward.

UPS and FedEx often employed contract language limiting a shipper’s ability to employ multiple carriers or renegotiate their incentives more than once every three years (this practice is still common). UPS, for example, often threatened a large monetary penalty if a shipper failed to use UPS for less than 95% (or more!) of their controllable package volume. When UPS and FedEx informed shippers in the run up to peak 2020 that they were suddenly unwilling to carry the packages demanded in their contracts, those shippers were left scrambling for options. Unfortunately, without alternate shipping contracts already in place, and with many smaller carrier networks already full, comparable alternatives were scarce and expensive. Still, if this had been the worst of it, fewer shippers might now be looking to eliminate UPS and FedEx from their supply chains.

Having scrambled to find capacity on short notice during the busiest time of the year, and in the middle of a pandemic, some shippers were horrified when UPS or FedEx returned months later threatening to exercise the anti-competitive penalty if the shipper failed to return the business UPS or FedEx had declined to carry. Others were forced to give up their hard-fought incentives in the middle of their contract term, resulting in unprecedented increases as high as 30%. An unfortunate few were hit with both. Multiple UPS account executives, frustrated with the way they were forced to treat their clients, or simply unhappy because UPS made no allowances in their commission structure for the package volume they were forced to turn away, explained in detail how UPS justified these increases by first altering their measures of profitability, then claiming the accounts were “unprofitable.”

Even companies unaffected by the volume caps, anti-competitive penalties, or mid-term contractual changes were still hit with extraordinary cost increases, including new surcharges, new triggers for old surcharges, general rate increases higher than any other year in the previous decade, and multiple increases to fuel surcharge tables expertly masked to appear unavoidable.

FIGURE 4:

SHADES OF A ’97 STRIKE

Before the Teamsters went on strike in 1997, UPS had a strong, 90-year-old reputation for reliability and practically uninterrupted service. When the Teamsters walked off the job to protest, among other things, UPS allegedly trying to save money by changing full-time jobs to part-time without reducing responsibilities, packages sat undisturbed on shipping docks for days. Service suffered until the Teamsters returned to work, despite the best efforts of UPS management to keep the network flowing. Many shippers viewed this not as a failure, but as a betrayal, and vowed to never do business with UPS again. A few months later, FedEx finalized the purchase of the parent company of RPS, rebranded it FedEx Ground, and began to create the first viable Ground competitor for UPS. Despite longer transit times and less reliable service, FedEx Ground acquired and kept many customers simply because of what it wasn’t: UPS.

Now, 25 years later, FedEx is joining UPS in making many of the same mistakes, including commoditizing customers and employees. This time, however, the barrier to entry for would-be competitors is lower, thanks to the internet, e-commerce, big data, 1099 employees, Amazon, and venture capital. Angry shippers looking for new alternatives not only have access to more companies, but also varied services across multiple business models.

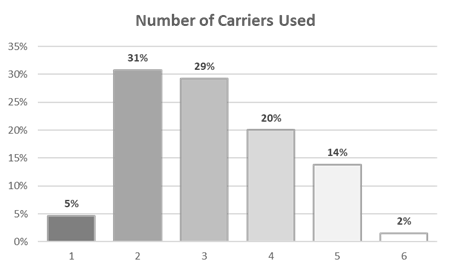

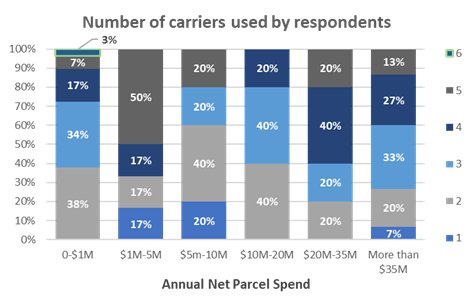

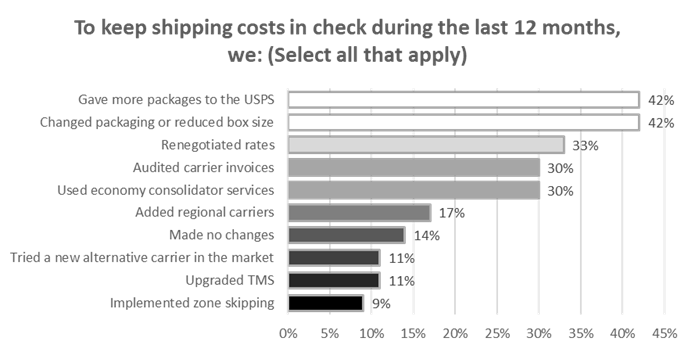

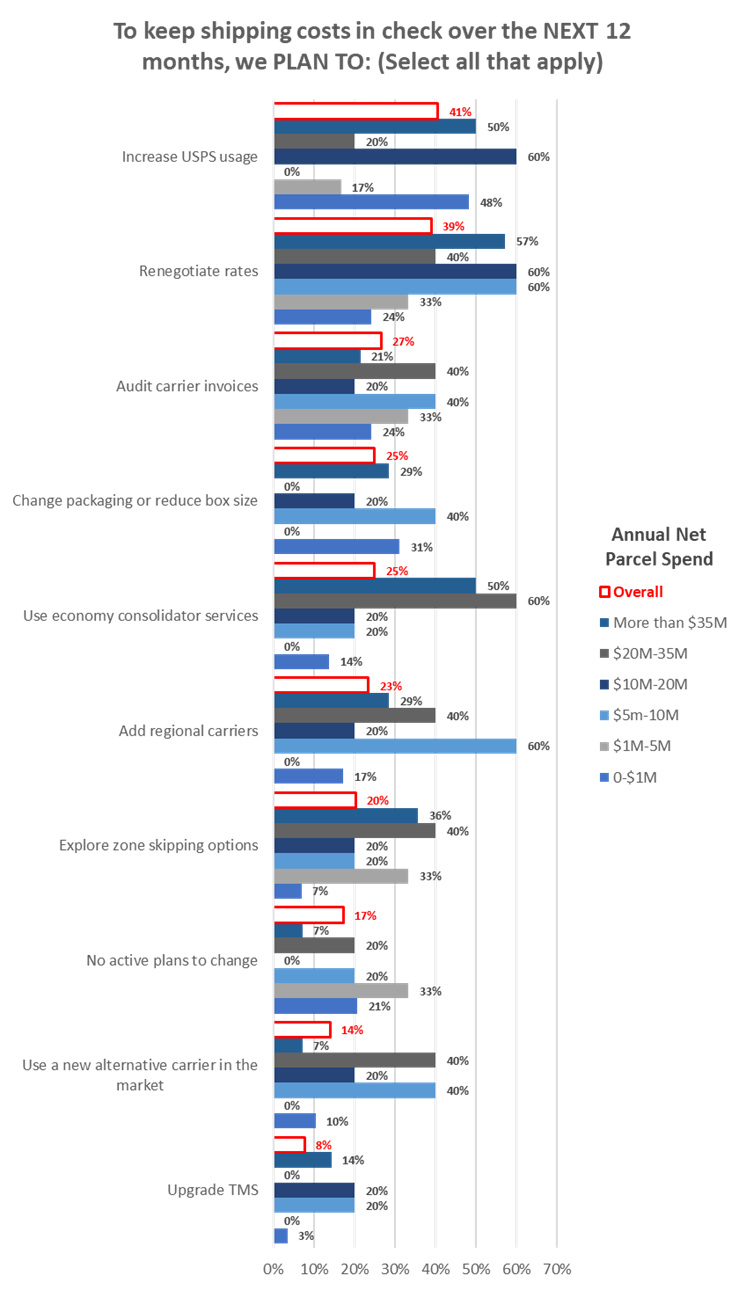

Over one third of respondents, 36%, already used four or more carriers (see Figure 5A.) Figure 6A shows what shippers have done in the past 12 months to cut costs, while Figure 6B shows what they plan to do in the next 12 months. Please note that economy consolidator services are DHL e-Commerce, OSM Worldwide, Pitney Bowes, etc.; regional carriers include LaserShip/OnTrac, LSO, GLS, Spee-Dee Delivery, etc.; and new alternative carriers are companies such as PARCLL, SmartKargo, X-Delivery, Sendle, Pandion, ShipX, Veho, etc.

FIGURE 5A:

Figure 5B:

Figure 6A:

Figure 6B:

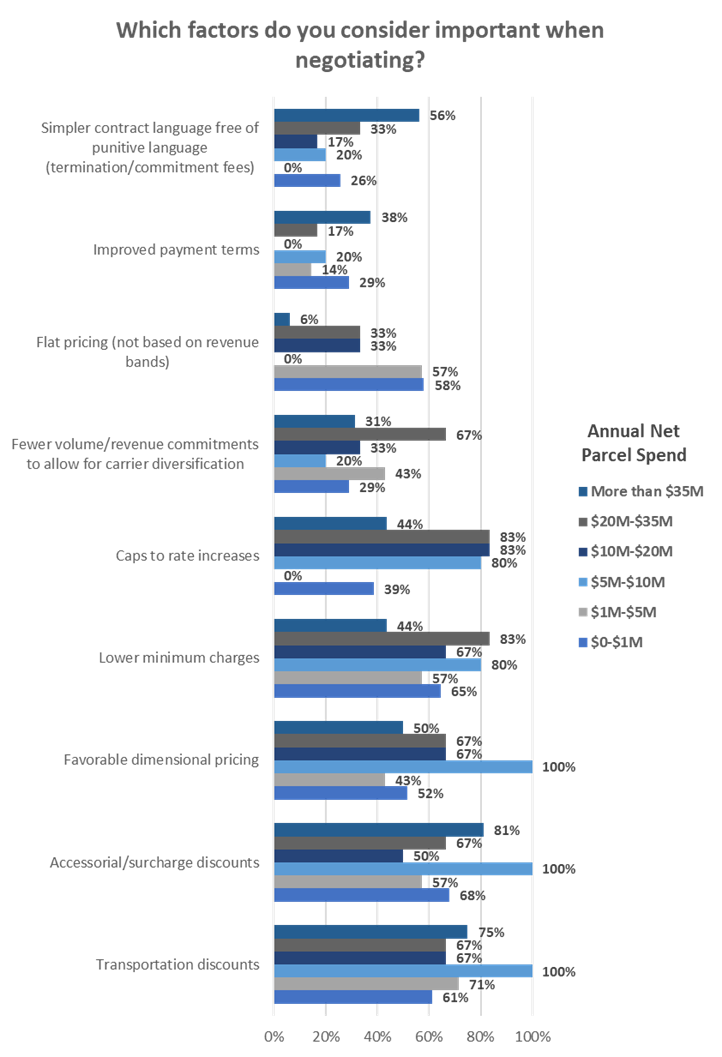

Figure 7 shows the concessions sought by shippers go beyond normal discounts to directly address the tactics UPS and FedEx deploy to improve their yield.

FIGURE 7:

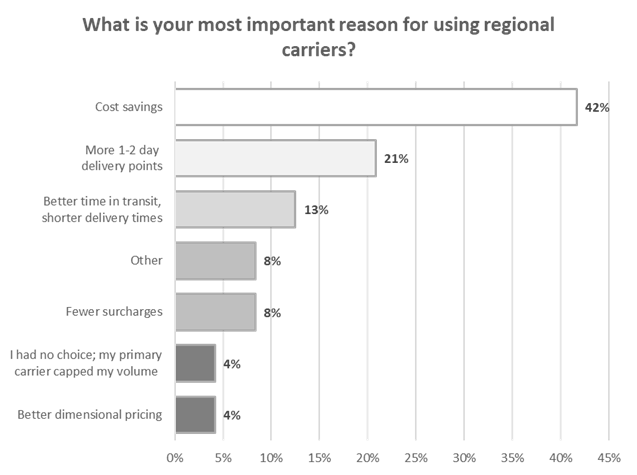

Many of these same requests may be unnecessary with alternative carriers, including simpler contracts free of punitive language, flat pricing, and fewer volume and revenue commitments. Alternative carriers also have lower list rates, fewer surcharges, and lower rates for the surcharges they do have. Additionally, many alternative carriers deliver faster within their geographic coverage than FedEx and especially UPS, allowing users to reduce service upgrades for next-day and two-day deliveries (see Figure 8A.)

FIGURE 8A:

Figure 8B

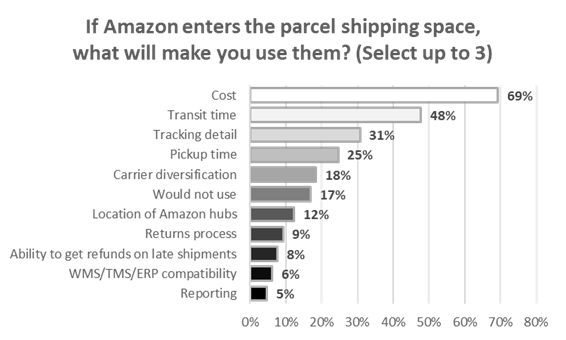

Price would also be the top reason for using Amazon Logistics if/when it becomes a general service offering.

SO, WHY ISN’T EVERYONE USING ALTERNATIVE CARRIERS?

UPS and FedEx have, in a sense, funded the rise of their new competition. Capping package volume forced some shippers to try carriers they never would have considered. Aggressive rate increases sent other shippers on an existential quest to find cheaper alternatives. And venture capital firms, which for years had been eyeing transportation as an industry overdue for disruption, have invested heavily as shipper frustration has grown.

The technology gap has narrowed. Most shippers now use a single platform to process packages for almost any carrier. Tracking services have been similarly consolidated. And while UPS and FedEx retain some advantages important to certain industries (e.g., healthcare), the differences fail to register for shippers in many other industries.

Plus, UPS and FedEx have encouraged shippers to fulfill from multiple locations by hiking up surcharges on longer zone shipments, making geographic coverage increasingly irrelevant, especially for larger shippers. As cross-country movements decline as a percentage of shipments and shippers gain access to new regional and local providers, many alternative carriers are proving just as capable of meeting shippers’ coverage needs as the legacy carriers. Still, executive leaders like Carol Tomé cling to the claim that shippers are willing to pay more for UPS’s increasingly irrelevant “end-to-end network.”

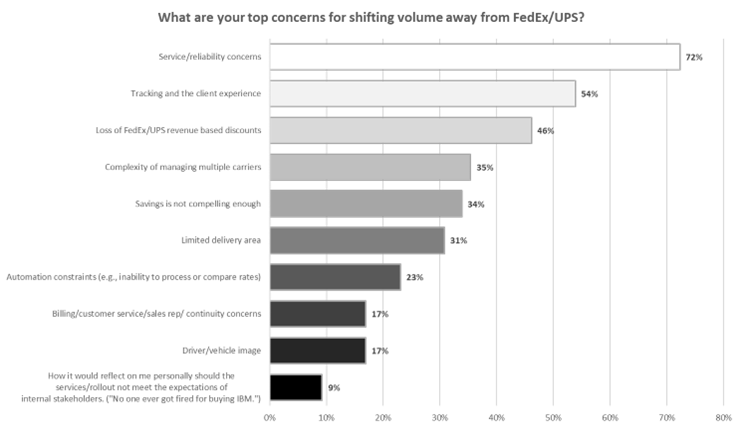

Despite all of this, it is still common for decision-makers to dismiss the idea of using any carrier other than UPS, FedEx, and occasionally the USPS. Some may hesitate based on old information (e.g., 72% of respondents cited service and reliability concerns as their top reason to stay with FedEx or UPS, and 17% cited concerns with driver or vehicle image), others may contend with inflexible IT systems (35% cited the complexity of managing multiple carriers, and 23% cited automation constraints), and many shippers have constraints placed upon them by contractual commitments or anti-competitive language in a UPS or FedEx contract (46% cited the loss of FedEx or UPS revenue-based discounts). See Figure 9 for these and other reasons.

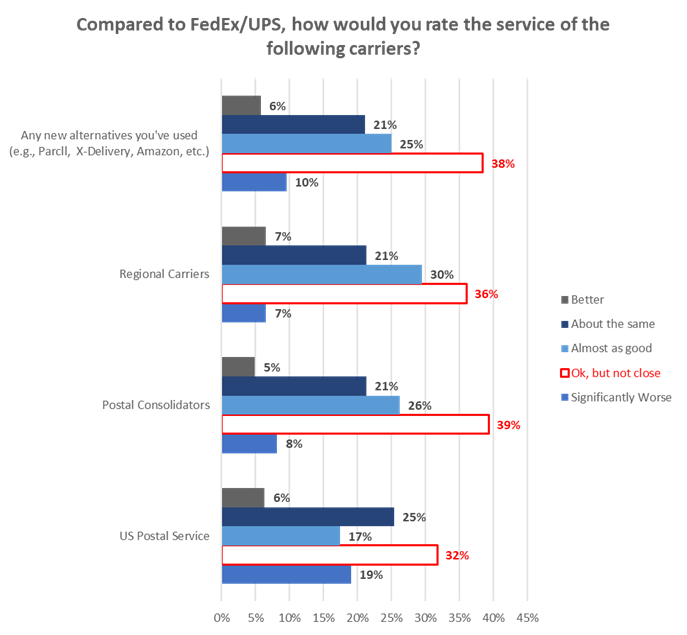

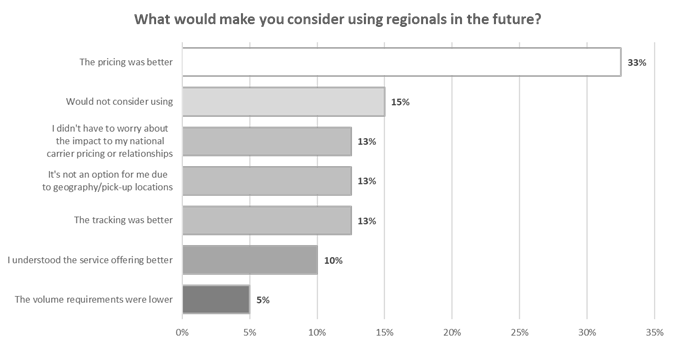

While perception concerns remain, alternative carriers are making progress. Roughly 30% of respondents rated the service of each alternative carrier type as better than, or about the same as, FedEx and UPS (see Figure 10), and only 15% of respondents said they would not consider using regional carriers in the future (see Figure 11).

FIGURE 9:

Figure 10:

Figure 11

THERE IS HOPE

As the industry becomes more competitive, UPS and FedEx will find it harder to increase prices as aggressively as they did from 2020 to 2022. Their value propositions will improve, forcing some of their new competitors to merge or exit. Ultimately, shippers and consumers will end up with more carrier and shipping options than they had before the COVID-19 pandemic, better overall service, and more reasonable rates.

Josh Taylor is Senior Director of Professional Services at Shipware. Visit www.shipware.com for more information.