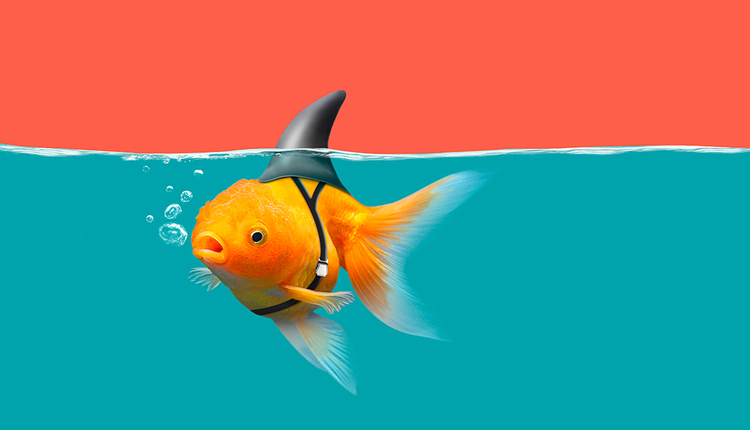

In literature, a cautionary tale is folklore embedded with a moral message. Obvious danger is ignored, and the main character meets its demise as a result of certain misgivings. The lesson to be learned, whether explicitly stated or implied, is clear in the end.

Amazon founder, Jeff Bezos, is a modern-day King Midas – but with a twist.

Amazon’s December announcement that it will expand its Amazon Air fleet from 40 to 50 (a 25% increase) came days after FedEx CEO Fred Smith downplayed any threat from the e-commerce giant.

“We don’t see them as a peer competitor at this point in time,” Smith told investors.

Yet, each day, it seems more likely that we will soon see what becomes of FedEx and UPS once Bezos gets his hands on the industry.

Can he turn cardboard into karats, or will the weight of the move prove too heavy for Amazon to sustain?

The world’s richest man, Bezos already has found his company on both sides of pressing societal issues.

Workers and politicians have raised concerns about conditions and pay, and small businesses have clamored that Amazon is forcing them to shutter their doors. Meanwhile, some 200 cities (more recently 20) have been at Bezos’ beckoning call in their attempts to land Amazon’s second headquarters in their respective cities.

Admiration or disdain for the company seems to depend on the lens through which one views it.

The American economy is founded upon capitalism and whether for or against the e-commerce giant, there is no arguing that Bezos – one of history’s greatest entrepreneurs – has capitalized.

By the end of 2017, Amazon employed 566,000 people; almost twice as many as the next eight leading global internet companies combined.

Still, the challenges that have surfaced during Amazon’s meteoric rise are real, and they prompt important questions that are impossible to answer but that must be discussed.

An Unprecedented Success?

Amazon’s success is what enterprise entrepreneurs dream of – the creation of something so impactful that it touches the lives of just about everybody. For this and many other reasons, it’s implausible to try and discern the appropriate gap between Bezos’ worth and employee pay, a controversial sticking point for those that feel Bezos’ wealth has come at the expense of workers that helped him create it. Employees will always lobby for more, as they should, and leaders will always push the company to become better than it was, as they should. When the proper balance is struck, chances are you’ll find yourself somewhere among the world’s most admired companies, like Amazon (and FedEx and UPS, too).

When Amazon announced that it would increase the minimum wage for all workers to $15 per hour, and subsequently confirmed that the change would indeed increase the total compensation for all works, it accomplished what few other companies have. It successfully used a pressing societal issue and turned it into widely regarded public relations success; one that stood up to pickets and politicians alike.

When companies grow to sizes the likes of Amazon, complicated management issues are inevitable. Compounding the challenge is the publicity associated with such scale. People at various companies are paid solely to cover that beat and report on anything they deem newsworthy, which largely results in scrutiny more than feel-good stories.

It’s only news if the man bites the dog, as the aphorism goes.

Then there’s the more macroeconomic issue of fairness. And in most small businesses’ cases, “The Amazon Effect” is a blend of survival of the fittest and keeping up with the times. There just isn’t enough evidence to support the fact that Amazon is putting small businesses out of business. In the span between when Amazon went public in 1997 and the end of 2015, the number of non-employer small businesses in America grew 57.6% to more than 24 million, despite the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression. (The number of employer small businesses has remained relatively constant over that time.)

According to a 2018 Feedvisor survey of mostly US-based Amazon sellers, almost half of all businesses generated 81 to 100% of their revenues from Amazon sales.

In the third quarter of 2018, Amazon generated $31.88 billion in third-party seller service revenue, up from $22.99 billion in the previous year. More than half of paid units sold on the Amazon platform were sold by third-party sellers, making it the company’s second-largest revenue segment behind Amazon Web Services.

In layman's terms, there’s a lot of gold going around.

Economics are governed by trade-offs. Amazon’s success has and will continue to generate new challenges for the company itself as well was others in the market.

There will continue to be plenty of storylines emerging from Amazon in the months ahead. Bezos’ demonstrated success navigating societal and political issues is an element that only adds to the tremendous viability of his leadership and Amazon’s presence within the complex global and economic and political landscapes.

Make no mistake, the burning question is and will continue to be: How will Amazon change shipping as we know it?

For Amazon, market entry will represent a significant separation from what thus far has been its core. Historically, that limits the odds of success for new ventures. Of course, Amazon isn’t most companies. While Fred Smith doesn’t see Amazon as a peer competitor “at this point in time,” that time is coming.

The irony of it all is that when the time does come, Amazon could very well make things better for businesses and employees. If it can deliver on its promise of cheaper shipping, then it would reverse a years-long trend of rising shipping costs that is among the leading culprits of businesses’ lagging profits during the digital age. With its investment in a second headquarters, the company has already promised tens of thousands of new jobs and economic investment in New York and Northern Virginia. The Amazon Air and Amazon Delivery Service Partner programs are sure to create additional employment opportunities.

It remains to be seen whether Bezos can turn package delivery into another Amazon gold mine, but here’s the twist:

Is Amazon ignoring the danger of market entry, or are established carriers FedEx and UPS ignoring the danger of underestimating a man who thinks he can make a golden 767 fly?

One thing is for sure: Someone is about to learn a valuable lesson.

Brandon Staton is an MBA candidate at The University of North Carolina Kenan-Flagler Business School and President and CEO of Shipmint, Inc., which helps corporate decision makers quickly connect with the industry’s top shipping consultants to save time and money. Visit www.goshipmint.com for more information.

This article originally appeared in the January/February, 2019 issue of PARCEL.